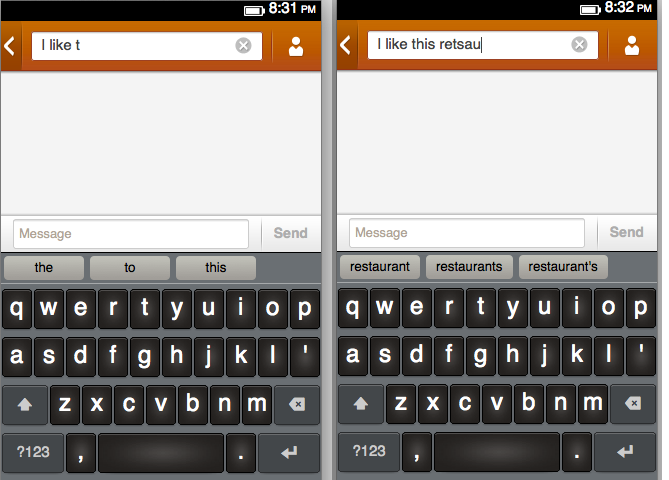

This was at IBM, New York where I was interning and working on the TJ Watson project. I returned back to my desk, turned on my dual monitors, started reading some blogs and engaging on Mozilla IRC (a new found and pretty short lived hobby). Just a few days before that, FirefoxOS was launched in India in the form of an Intex phone with a $35 price tag. It was making waves all around, because of its hefty price and poor performance . The OS struggle was showing up in the super low cost hardware. I was personally furious about some of the shortcomings, primarily the keyboard which at that time didn’t support prediction in any language other than English and also did not learn new words. Coincidentally, I came upon Dietrich Ayala in the FirefoxOS IRC channel, who at that time was a Platform Engineer at Mozilla. To my surprise he agreed with many of my complaints and asked me if I want to contribute my ideas. I very much wanted to, but then again, I had no idea how. The idea of contributing to the codebase of something like FirefoxOS terrified me. He suggested I first send a proposal and then proceed from there. With my busy work schedule at IBM, this discussion slipped my mind and did not fully boil in my head until I returned home from my internship.

Fast forward a couple of years. And now we don’t have a FirefoxOS anymore. So I decided about time I give a go about what went into the implementation. And get to the nitty gritty of the code.

Each word in the dictionary has a frequency associated with it, for example, the top words in the English dictionary are:

WordFrequency

the 222

of 214

and 212

in 210

a 208

to 208

For example, if you type “TH”, the program will suggest you “the” and “this” (with frequencies of 222 and 200), but not something rare like “thundershower” (which has a frequency of 10).

Mozilla developers previously used a Bloom filter for this task, but then switched to DAWG.

Using DAWG, you can quickly find mistyped words, however you cannot easily find the most frequent words for a given prefix. The existing implementation of DAWG in Firefox OS code (made by Christoph Kerschbaumer) worked like this: each word had its frequency stored in the last node of the word; the program just traversed the whole subtree and looked for three most frequent words. To make the tree traversal feasible, it was limited to two characters, so the program was able to suggest only 1-2 characters to finish the word typed by user.

Dictionary size was another problem. Each DAWG node consisted of the letter, frequency, left, right, and middle pointers (four bytes each; 20 bytes in total). The whole English dictionary was around 200'000 nodes or 3.9 MB.

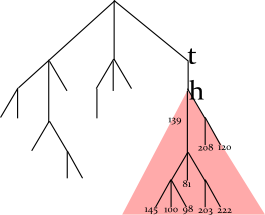

In this example, the program looks up the prefix TH in the tree, enumerates all words in the dictionary starting with TH (by traversing the red subtree), and find three words with maximum frequencies. For the full English dictionary, the size of subtree can be very large.

Sorting nodes by maximum frequency of the prefix

Here is what I proposed and implemented for Firefox OS.

If you can find a way to store the nodes sorted by maximum frequency of the words, then you can visit just the nodes with the most frequent words instead of traversing the whole subtree.

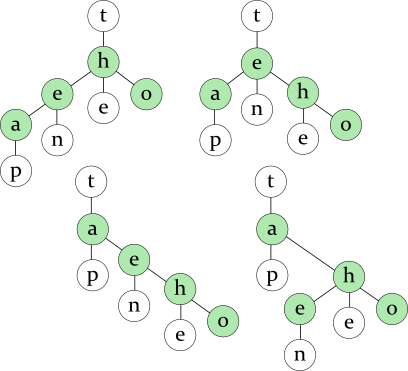

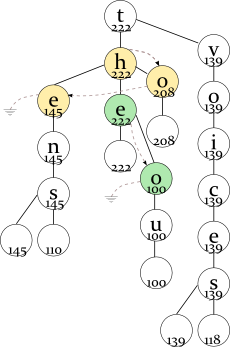

Note that a TST can be viewed as consisting of several binary trees; each of them is used to find a letter in the specific position. There are many ways to store the same letters in a binary tree (see green nodes on the drawing), so several TSTs are possible for the same words:

Words: tap ten the to

Usually, you want to balance the binary tree to speed up the search. But for this task, I thought to put the letter that continues the most frequent word at the root of the binary tree instead of perfectly balancing it. In this way, you can quickly locate the most frequent word. The left and the right subtrees of the root will be balanced as usual.

However, the task is to find the three most frequent words, not just one word. So you can create a linked list of letters sorted by the maximum frequency of the words containing this letters. An additional pointer will be added to each node to maintain the linked list. The nodes will be sorted by two criteria: alphabetically in the binary tree (so that you can find the prefix) and by frequency in the linked list (so that you can find the most frequent words for this prefix).

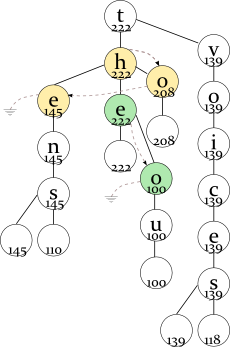

For example, there are the following words and frequencies:

the 222thou 100

ten 145to 208 tens 110

voices 118voice 139

For the first letter T, you have the following maximum frequencies (of the words starting with this prefix):

- TH — 222 (the full word is “the”; “thou” has a lower frequency);

- TO — 208 (the full word is “to”);

- TE — 145 (the full word is “ten”; “tens” has a lower frequency).

The node with the highest maximum frequency (H in “th”) will be the root of the binary tree and the head of the linked list; O will be the next item, and E will be the last item in the linked list.

So you have built the data structure described above. To find N most frequent words starting with a prefix, you first find this prefix in the DAWG (as usual, using the left and right pointers in the binary tree). Then, you follow the middle pointers to locate the most frequent word (remember, it's always at the root of the binary tree). When following this path, you save the second most likely nodes, so that after finding the first word, you already know where to start looking for the second one.

Please take a look at the drawing above. For example, the user types the letter T. You go down to the yellow binary tree. In its root, you find the prefix of the most frequent word (H); you also remember the second most likely frequency (208 for the letter O) by looking in the linked list.

You follow to the green binary tree. E is the prefix of the most frequent word here; you also remember the second frequency (100 for the letter O). So, you have found the first word (THE). Where to look for the second most frequent word? You compare the saved frequencies:

tho 100

to 208

and find that TO, not THO is a prefix of the second most frequent word.

So you continue the search from the TO node and find the second word “to”. TE is the next node sorted by frequency in the linked list, so you save it instead of TO:

tho 100

te 145

Now, TE has greater frequency, so you choose this path and find the third word, “ten”.

You can store the candidate prefixes in a priority queue (sorted by the frequency) for faster retrieval of the next best candidate, but I chose a sorted array for this task, because there are just three words to find. If you already have the required number of candidates (three) and you found a candidate that is worse the already found candidates, you can skip it. Don't insert it at the end of the priority queue (or the sorted array), because it will not be used anyway. But if you found a candidate that is better than the already found ones, you should store it (it's possible to replace the worse candidate in this case). So you can store just three candidates at any time.

The advantage of this method is that you can find the most frequent words without traversing the whole subtree (not thousands of nodes, but typically less than 100 nodes). You also can use fuzzy search to find a prefix with possible typos.

Averaging the frequency

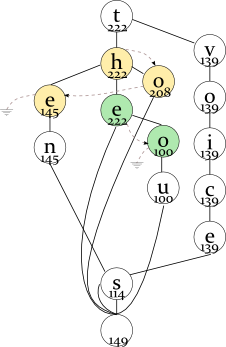

Another problem is the file size and the suffixes (such as “-ing”, “-ed”, and “-s” in English language). When converting from TST to DAWG, you can join together the suffixes only if their frequencies are equal (the previous implementation by Christoph Kerschbaumer used this strategy), or you can join them if their order in the linked list is the same and store the average frequency in the compressed node.

In the later case, you can reduce the number of the nodes (in the English dictionary, the number of nodes went from 200'000 to 130'000). The frequencies are averaged only if doing so does not change the order of words (a less frequent suffix is never joined with a more frequent suffix).

For example, consider the same words:

the 222thou 100

ten 145to 208 tens 110

voices 118voice 139

The prefix “-s” has an average frequency of (110+118)/2=114 and the null ending (the end of the word) has an average frequency of (222+100+208+145+110+139+118)/7=149, so the latter will be suggested more often.

The nodes are joined together only if their subtrees are equal and the linked lists are equal. For example, if “ends” were more likely than “end”, it would not be joined with “tens” that is less likely than “ten”. The averaging changes frequencies, but preserves the relative order of words with the same prefix.

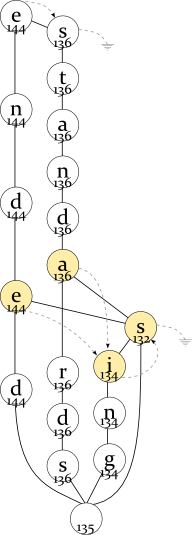

The program is careful enough to preserve the linked lists when joining the nodes. But if the linked lists are partially equal, it can join them. Consider the following example (see the drawing to the right of this text):

ended 144ending 135

standards 136ends 130 standing 134

stands 133

The “-s” node has the averaged frequency of round((133+130)/2)=132, and “-ing” nodes have round((134+135)/2)=134. The linked lists and the nodes are partially joined: the common part of “standARDS — standING — standS” and “endED — endING — endS” is “-ing”, “-s”, and this part is joined. Again, if “standing” were more likely than “standards” or less likely than “stands”, it would be impossible to join the nodes, because their order in the linked list would be different.

Besides that, I allocated 20 bits (two bytes + additional four bits) for each pointer instead of 32 bits. Sixteen bits (65'536 nodes) were not enough for Mozilla dictionaries, but twenty bits (1 million nodes) are enough and leave a room for further expansion. The nodes are stored as a Uint16Array, including the letter and the frequency (16 bits each), the left, the right, the middle pointer, and the pointer for the linked list (the lower 16 bits of each pointer). An additional Uint16 stores the higher four bits of each pointer (4 bits × 4 pointers). After these changes, the dictionary size went down from the initial 3.9 MB to 1.8 MB.

Conclusion

The optimized program is not only faster but also uses a smaller dictionary.

This finishes up on how we can optimize it. Then comes the learning part. You can have a look at my talk which has a working demo as well on how it works. And specially with Bengali too

Acknowledgements:

The following people have guided me on this course and I am forever grateful to them for whatever I could do in the project

JSFoo 2015

OpenSource Bridge 2015

The following people have guided me on this course and I am forever grateful to them for whatever I could do in the project

- Dietrich Ayala - To actually help me start the project. getting me connected to everyone who helped me

- Indranil Das Gupta - For valuable suggestions and also helping me get FIRE corpus

- Sankarshan Mukhopadhyay - Valuable suggestions on my method and pointing out related work in Fedora

- Prasenjit Majumder, Ayan Bandyopadhyay - For getting me access to the FIRE corpus

- Tim Chien and Jan Jongboom - I learned from their previous works and for handling all my queries

- Mahay Alam Khan - For getting me in touch with Anirudhha

- Countless people in #gaia in Mozilla IRC who patiently listened to all my problems while I tried to build gaia in a Windows machine (*sigh*) and later all the installation problems

I gave two talks on the related topic.

The OSB talks was my first time speaking in a conference, so you can visibly see how sloppy I am. By JSFoo, I was a little experienced (one talk experience) so became little less sloppy (still plenty).

Another derivation I did present in OpenSource HongKong. But I don't believe that is recorded anywhere.JSFoo 2015

OpenSource Bridge 2015